In 1900, the average American lived to 47. By 2000, life expectancy had reached 77—a gain of three decades in a single century. While many factors contributed to this remarkable leap, historians and epidemiologists consistently point to one intervention above all others: antibiotics. These drugs didn't just treat infections; they fundamentally transformed what it meant to grow old. Yet a century later, longevity scientists are uncovering an uncomfortable irony. The very medications that helped us live longer may be quietly undermining how well we age.

The Original Longevity Drug

Before penicillin's discovery in 1928, a scratch from a rose thorn could prove fatal. Pneumonia killed one in four who contracted it. Tuberculosis was a death sentence. Childbirth routinely claimed mothers to puerperal fever. Antibiotics changed everything. Suddenly, infections that threatened lives for millennia became manageable inconveniences. Children survived to adulthood. Adults survived to old age. If any drug deserves the title of "longevity intervention," it's antibiotics.

Today, most of us have taken antibiotics multiple times—amoxicillin for strep throat, a Z-pack for bronchitis, ciprofloxacin for a urinary tract infection, or perhaps months of doxycycline for acne. In 2010, American physicians wrote 258 million outpatient antibiotic prescriptions. These drugs remain essential: they still save countless lives from bacterial pneumonia, sepsis, and serious infections. The question longevity researchers are now asking isn't whether antibiotics work; they're asking what else they're doing.

The Microbiome and the Science of Aging Well

The emerging science of healthspan—not just how long we live, but how many years we spend in good health—has placed the microbiome at center stage. The trillions of bacteria inhabiting our gut and skin aren't passive passengers. They produce vitamins, train our immune systems, regulate metabolism, and communicate with our brains through the gut-brain axis. Research now links microbiome composition to conditions once considered inevitable consequences of aging: chronic inflammation, metabolic dysfunction, cognitive decline, and immune senescence.

Research published in Nature Reviews Microbiology demonstrates that even a single course of broad-spectrum antibiotics can alter gut microbiome composition for weeks to months. Some bacterial populations may never fully recover, particularly after repeated exposures. Antibiotics like amoxicillin and fluoroquinolones are especially disruptive because they kill indiscriminately, eliminating beneficial species, as well as pathogens. Each course, however medically necessary, leaves a lasting imprint on the microbial ecosystem that increasingly appears central to aging well.

Studies in Frontiers in Microbiology have linked antibiotic-induced dysbiosis to increased risk of inflammatory conditions, metabolic disorders, and impaired immune function—the very hallmarks of accelerated biological aging. Early-life antibiotic exposure has been associated with elevated rates of obesity, asthma, and allergies later in life. The picture emerging from longevity science suggests that microbial diversity may be a biomarker of healthy aging—and antibiotics, for all their benefits, work against it.

Where Longevity Meets Dermatology

The skin, our largest organ, hosts its own complex microbiome—and it's here that antibiotic use patterns differ most dramatically from other medical contexts. While a course of antibiotics for strep throat lasts 10 days, acne and rosacea have traditionally been treated with antibiotic regimens lasting months or even years. Dermatologists prescribe more oral antibiotic courses per clinician than any other specialty, with tetracyclines like doxycycline and minocycline comprising 75% of prescriptions.

For decades, this approach made sense. Antibiotics can suppress Cutibacterium acnes, reduce inflammation, and clear skin. This does work. But the longevity lens raises new questions. If microbial diversity supports healthy aging, what are the cumulative effects of extended antibiotic exposure?

For individuals concerned with optimizing their healthspan, the question is: can precision alternatives offer comparable benefits with less microbial disruption?

Precision Medicine for the Longevity Era

The longevity medicine movement emphasizes interventions that optimize long-term health rather than merely treating symptoms. Applied to skin conditions, this philosophy asks: can we address the root microbial causes of acne, rosacea, and other inflammatory issues without collateral damage to the broader ecosystem?

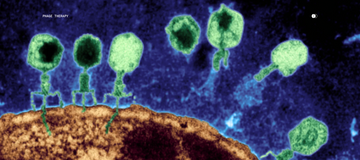

Bacteriophage therapy offers one compelling answer. Phages are nanomicrobes that naturally target specific bacteria with remarkable precision—eliminating targeted pathogens while leaving beneficial microorganisms untouched. A 2023 study in Nature Communications demonstrated that topical phage therapy in a mouse model of C. acnes-induced acne reduced inflammation and improved outcomes without the broad microbial disruption of antibiotics.

Parallel Health is pioneering this precision approach with a focus on long-term skin health. Our platform combines advanced microbiome testing—providing strain-level analysis of each patient's unique skin ecosystem—with AI-driven insights and targeted phage therapy. Rather than carpet-bombing the skin's microbial community with broad-spectrum antibiotics, our Microbiome Dermatology™ approach identifies specific problematic strains and addresses them precisely. It's an approach aligned with a longevity ethos; that is, optimize the system rather than override it.

Rethinking the Standard of Care in Dermatology

Antibiotics remain essential for serious bacterial infections and will continue saving lives. The question isn't whether to abandon antibiotics but whether we can be more strategic – to preserve their power for situations that truly require it while pursuing targeted alternatives for chronic conditions.

The next frontier is developing precision tools that work with the body's microbial ecology rather than against it. For those who view health through the lens of longevity and healthspan, protecting microbial diversity while treating skin conditions isn't just about clearer skin—it's about optimizing the ecosystem that may shape how well we age.

Frequently Asked Questions

How does the microbiome affect aging?

The gut and skin microbiomes influence immune function, inflammation levels, metabolism, and even cognitive health—all factors associated with biological aging. Research suggests that microbial diversity tends to decline with age, and that maintaining a healthy microbiome may support healthspan. Centenarian studies have found distinctive microbiome signatures in exceptionally healthy older adults.

Which antibiotics have the biggest impact on the microbiome?

Broad-spectrum antibiotics cause the most disruption. These include amoxicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanate (Augmentin), fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin), and clindamycin. Narrow-spectrum antibiotics targeting specific bacteria types cause less collateral damage to beneficial microbes.

How long does it take for the microbiome to recover after antibiotics?

Most bacterial populations begin recovering within weeks, though full recovery can take months. Some studies suggest certain species never return to pre-treatment levels, particularly after repeated courses. Recovery varies based on antibiotic type, duration, diet, and individual factors.

What is phage therapy?

Bacteriophages are nanomicrobes that infect and destroy specific bacteria without harming other microorganisms. Unlike broad-spectrum antibiotics, phages target only their designated bacterial hosts, leaving beneficial microbes intact. This precision makes phage therapy attractive for conditions requiring long-term treatment.

How does Parallel Health's microbiome testing support longevity goals?

Parallel's microbiome testing for face, body, scalp, and odor provides strain-level analysis of the bacteria, viruses, and fungi on your skin, revealing which specific organisms may be driving inflammation or skin issues. Board-certified dermatologists and microbiology experts then use this quantitative data to design targeted interventions—including precision phage therapy—that eliminate problematic microbes while preserving the beneficial ones. The result is healthier, more resilient skin, without the microbial collateral damage that longevity research increasingly links to accelerated aging.

References

1. Barbieri JS, Spaccarelli N, Margolis DJ, James WD. Trends in Oral Antibiotic Prescription in Dermatology, 2008 to 2016. JAMA Dermatology. 2019;155(3):290-297. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4944

2. Francino MP. Antibiotics and the Human Gut Microbiome: Dysbioses and Accumulation of Resistances. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2016;6:1543. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2015.01543

3. Ramirez-Sanchez D, Gutierrez-Castrellon P, et al. Antibiotics as Major Disruptors of Gut Microbiota. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 2020;10:572912. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2020.572912

4. Rimon A, Rakov C, Lerer V, et al. Topical phage therapy in a mouse model of Cutibacterium acnes-induced acne-like lesions. Nature Communications. 2023;14:1005. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-36694-8

5. Castillo DE, Nanda S, Keri JE. Propionibacterium (Cutibacterium) acnes Bacteriophage Therapy in Acne: Current Evidence and Future Perspectives. Dermatology and Therapy. 2019;9(1):19-31. doi:10.1007/s13555-018-0275-9

6. Dessinioti C, Katsambas A. Antibiotics and Antimicrobial Resistance in Acne: Epidemiological Trends and Clinical Practice Considerations. Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine. 2022;95(4):429-443.

7. Golembo M, Puttagunta S, Rappo U, et al. Development of a topical bacteriophage gel targeting Cutibacterium acnes for acne prone skin and results of a phase 1 cosmetic randomized clinical trial. Skin Health and Disease. 2022;2(2):e93. doi:10.1002/ski2.93

8. Fishbein SRS, Mahmud B, Dantas G. Antibiotic perturbations to the gut microbiome. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2023;21:772-788. doi:10.1038/s41579-023-00933-y